Should I not have Pity?

In an article for Yom Kippur 5774, Rabbi Cherki explains that Jonah placed greatest emphais on truth, while G-d wanted to teach him the trait of mercy.

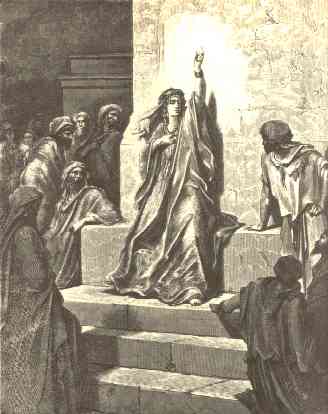

What did the Prophet Jonah think in principle? Why did he try to flee instead of observing the direct command given to him by G-d, to make a proclamation to Nineveh as he had been told to do? Can his objections really be limited to the well-known consideration that since “Gentiles are close to teshuva (repentance)” their action will serve as a basis for criticism of the children of Israel? Didn’t Jonah want, like all the prophets of Israel, to improve the entire world?

Perhaps the answer is that Jonah was upset by the very nature of the repentance that might be expected from the people of Nineveh. It would be nothing more than a simplified caricature of real teshuva. Clearly, the people of Nineveh acted out of a sense of fear, not out of love of G-d. They did not even act out of a proper fear of G-d, which leads to an ethical modification of the soul, but rather out of a fear of a physical danger which must be removed. But even so, this repentance, which was superficial in nature, was accepted by the Holy One, Blessed be He. Nineveh was given an extension, and later on they were the ones who destroyed the Kingdom of Samaria.

However, in spite of the logic of this explanation, there is absolutely no hint of these ideas in the text. The straightforward reading of the text implies that Jonah objected to the basic concept of accepting the teshuva of the people. “Therefore I moved quickly, to flee to Tarshish, for I know that you are G-d, who has mercy and shows pity, is very patient and full of kindness, and willing to forgive evil” [Jonah 4:2]. In this list of G-d’s traits, Jonah leaves out the characteristic “truth” which appears in the similar list in the Torah.

His very name shows that as a dove (a “yonah“) he is faithful to his mate, to the truth. He is the son of “Amitai” – from the word “emet,” truth.

The trials that Jonah is put through are all pointed at giving him a greater sense of a love for life, in preference to his love for truth. First, the storm is an expression of the living power of the sea. This is followed by a fish which swallows him, a living creature that protects him from death. Then there is “a pregnant fish which has in it six hundred thousand baby fish” (Midrash), and finally he is protected by a castor oil plant, which makes him very happy. For life to exist, it is necessary to have a large measure of mercy. “If you want judgment, the world cannot exist. If you want a world, there can be no true judgment.” [Bereishit Rabba, Vayeira].

The logical inference of a “kal vachomer” is also used to convince Jonah to accept the legitimacy of the trait of mercy. “You had pity on the castor oil plant… Should I not have pity on Nineveh?” [Jonah 4:10-11]. At this point, the book of Jonah ends without any response by the prophet. One who insists on the supremacy of truth, as opposed to the desire of the Holy One, Blessed be He, to accept those who repent, has no answer. In the Maftir reading from the Prophets for Yom Kippur, our tradition fills in what is missing by adding the “Thirteen Traits of Mercy” listed in the book of Micah, almost as if Jonah had recited them. As is written, “Jonah immediately prostrated himself on his face, and he said, rule Your world with the trait of mercy” [Yalkut Shimoni, Yonah 4:551].

See how great teshuva is, it takes precedence over the trait of truth, so that the world will continue to exist.

(With thanks to Rabbi Yosef Aton for some of the above ideas.)

Source: “AS SHABBAT APPROACHES” – a biweekly column in Shabbat B’Shabbato, Yom Kippur 5774, Volume 1491. (Zomet Institute) See: www.zomet.org.il/eng